“Slow worm!” someone calls and a few of us gather round to try and catch a glimpse before the creature slithers away. Slow worm is not a particularly accurate name for a species that is often mistaken for a snake, and is in fact, a legless lizard that can move pretty quickly when it wants to. But apparently the name has nothing to do with speed but derives from an old English word "slāwyrm", where slā- means 'earthworm' or 'slowworm' and wyrm means "serpent, reptile".

We’re at Shirley Heath today, removing bracken to give the heather more chance to flourish. Bracken-pulling is a satisfying task, especially when the ground is as soft as it is here, and the stems come out easily, roots and all. It’s possible to make a big impact in a short space of time.

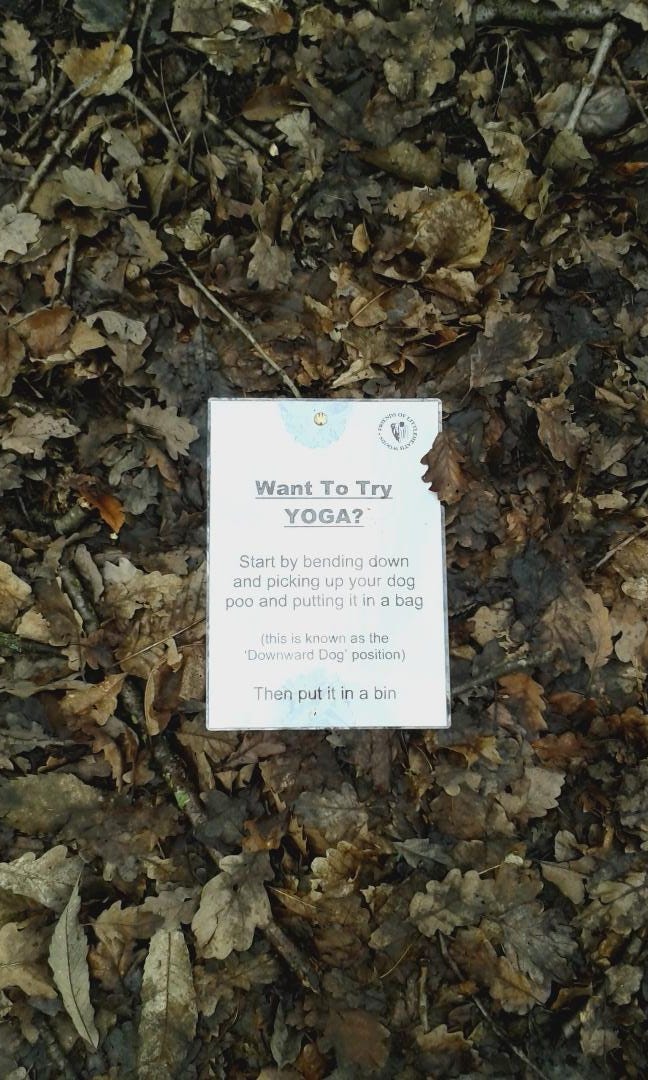

Later, we find another slow worm which has to be moved to somewhere it won’t be disturbed so I manage to get a better picture. We find a toad too, nestled in the leaf litter among the heather. But as we clear more of the area, we also make lots of far less pleasant discoveries. Hidden in the undergrowth are dozens and dozens of bags of dog poo. It seems that many of the local dog walkers have only absorbed part of the ’Bag it and Bin it’ message and rather than finding a bin for their pet’s deposits they have simply slung the filled bag into the scrubby area next to the path.

The poo-bag chuckers of Shirley Heath might argue in their defence that there are no bins nearby but while you might reasonably expect to have those provided in a park, this area of heathland surrounded on most sides by woodland feels more like open countryside than a park. Visiting for the first time since I learnt about Addington Golf Club’s controversial proposals to create a driving range and irrigation pond here a few months ago, I’m reminded again just how important it is to have open spaces like this, both to give those of us who live in more built-up areas easy access to a slightly wilder landscape, and to provide places where slow worms, toads and many other species can thrive. Thankfully the golf club failed in their attempt to take over the management of Shirley Health and “improve” the area in return for being allowed to develop part of it.

Apart from a little bracken removal every now and then the Heath doesn’t need any improving, certainly not of the kind the golf club proposed. It is clearly already valued, and much used, by people who live on the nearby housing estate, particularly those of them who own dogs. There were lots of dogs and their owners out for a walk while we were working there. There was also lots of evidence, that many of these dogs had not been particularly well-trained and sadly, it’s not uncommon for us to experience poorly trained dogs at many of the sites where we volunteer. Even when dogs are well-behaved, the sheer number of canine visitors can still have an impact on wildlife in some places, deterring ground-nesting birds and other species such as hedgehogs which are particularly sensitive to disturbance. At Farthing Downs, near Happy Valley, another popular place for dog-walkers, sections of the downs are now fenced off each Spring to ensure there are places the skylarks can breed in relative peace.

Then there is the impact of what dogs leave behind. Dog faeces and urine contain nitrogen and phosphorus, high levels of which can result in over-fertilisation of the soil, and lead to an over-abundance of plants like nettles which thrive on these nutrients. Nettles are not necessarily a bad thing - they are the food plant for the caterpillars of certain butterfly species - but it’s never good for biodiversity if they are able to outcompete plants which need a low nutrient environment.

According to the charity Plantlife, over two-thirds of British wild flowers require low or medium levels of nitrogen and over 93% of sensitive habitat areas in England and Wales already experience excessive levels of nitrogen. Plantlife is calling for a range of actions to address this including the introduction of statutory action plans to reduce local emissions and restore damaged habitats in severely-affected areas. Their focus seems to be very much on the build-up of nitrogen in the atmosphere resulting from transport, industry, and intensive farming, but it seems we should also be paying more attention to what’s happening at ground level.

Research in nature reserves in Belgium a couple of years ago identified levels of nitrogen and phosphorus resulting from dog deposits which would be illegal on farmland, and which created similar levels of pollution as industry and traffic fumes. Even conscientious dog owners could be unwittingly damaging local biodiversity as keeping dogs on leads concentrates the nutrient levels in areas near footpaths, and picking up dog poo only partially reduces the impact as the urine also contains high levels of nitrogen and it is impossible to take that away.

So, what can be done about this? Should we be banning dogs from certain sensitive sites to give other species more chance to thrive? That’s certainly what the Right to Roam campaign is calling for. They argue that making more areas of the countryside available for public access would mean that it would also be possible to have more places from which dogs are excluded in order to protect wildlife or livestock. The campaigners are also calling for the return of dog licences and for potential dog owners to be required to learn how to train their dogs as part of the application process. Requiring owners to take more responsibility for their dog’s behaviour could make a big difference if implemented effectively and while it would be hard to exclude dogs from places like Shirley Heath which are mainly visited by people who live very locally, increasing access to the surrounding countryside might make it possible to exclude dogs from some of the other sensitive nature-rich sites on the edge of London. But if those exclusions are going to be effective, there would need to be sufficient staff resources to ensure they are enforced effectively, and I’m not convinced they would be available.

What is clear is that this is an issue that needs to be addressed. Approximately a third of households in the UK own a dog. Ownership has increased in recent years, partly as a result of people acquiring dogs during lockdown, and new owners are more likely to live in urban areas so the pressure on open spaces in our towns and cities is increasing. Even though I don’t own a dog myself I recognise the valuable role that dog ownership plays for many people – providing companionship for the lonely and encouraging the inactive to get out-of-doors. But I also want to live in a country where lots of other species can thrive, even if that sometimes means placing restrictions on humans and our canine companions.

To finish….

…a few things I’d like to share:

Can writers save the planet? The Rare Earth series on Radio 4 covers lots of interesting topics on nature and the environment but I particularly enjoyed this episode on nature-writing which includes Mark Cocker, Phillipa Forrester and Chris Thorogood. Among other things, it includes a discussion about the purpose of nature writing and the extent to which it should aim to highlight the threats to the natural world as well as celebrating it. There are also some interesting points made about urban areas often being more biodiverse than parts of the countryside these days.

Big Butterfly Count: A reminder that Butterfly Conservation’s annual opportunity to contribute to species records by spending 15 minutes counting butterflies begins this Friday (12 July). It runs to 4 August, so you’ve got a few weeks to participate.

Flower-Insect Timed (FIT) Counts: This is another great opportunity to contribute to citizen science even if you haven’t got much time available. All you need to do is spend 10 minutes watching flowers and insects when the weather is good and you can do it anywhere – in your garden, the local park, or while out for a country walk. There’s all the information you need here.

Thank you for raising this difficult and sensitive issue in such a measured way. As you say dogs are great companion animals and dog walkers can help to make our urban wild places feel more populated and safer. But, as a bird watcher who is often just standing, looking through binoculars, I am frequently confronted by aggressive behaviour from dogs, who see a person lurking on the path as a threat.

As well as the pollution from dog pee and poo, there is the lesser known issue of the toxic pesticides in flea treatments. If a dog swims in a pond or river within a few days of being treated, these chemicals, which are highly poisonous to aquatic life, get washed into the water with potentially devastating effects. See this article on the Veterinary Prescriber website https://www.veterinaryprescriber.org/safedogswimming#:~:text=2.,(48%20hours)%20after%20treatment.

I think part of the answer is in educating dog owners from the start. It never works well when people are confronted on the spot! All new dog owners should be given an information pack which includes their responsibilities to wildlife, the environment and other people. Wildlife organisations could also do a lot more with information boards and signs, and finding ways to engage directly with local dog owners to explain the issues.