The Victorian naturalist, Richard Jefferies, was born in 1848 on a small Wiltshire farm but spent part of his childhood living with relatives in Sydenham not far from where I live in South London. Aged 16, he attempted to run away to France with his cousin as part of a plan to walk to Russia. But both that and a later bid to go to America failed because the teenagers had very little money. After returning to the family farm, Jefferies found work as a newspaper reporter, a job which would lead to him pursuing a career as a writer and publishing numerous books of both fiction and non-fiction.

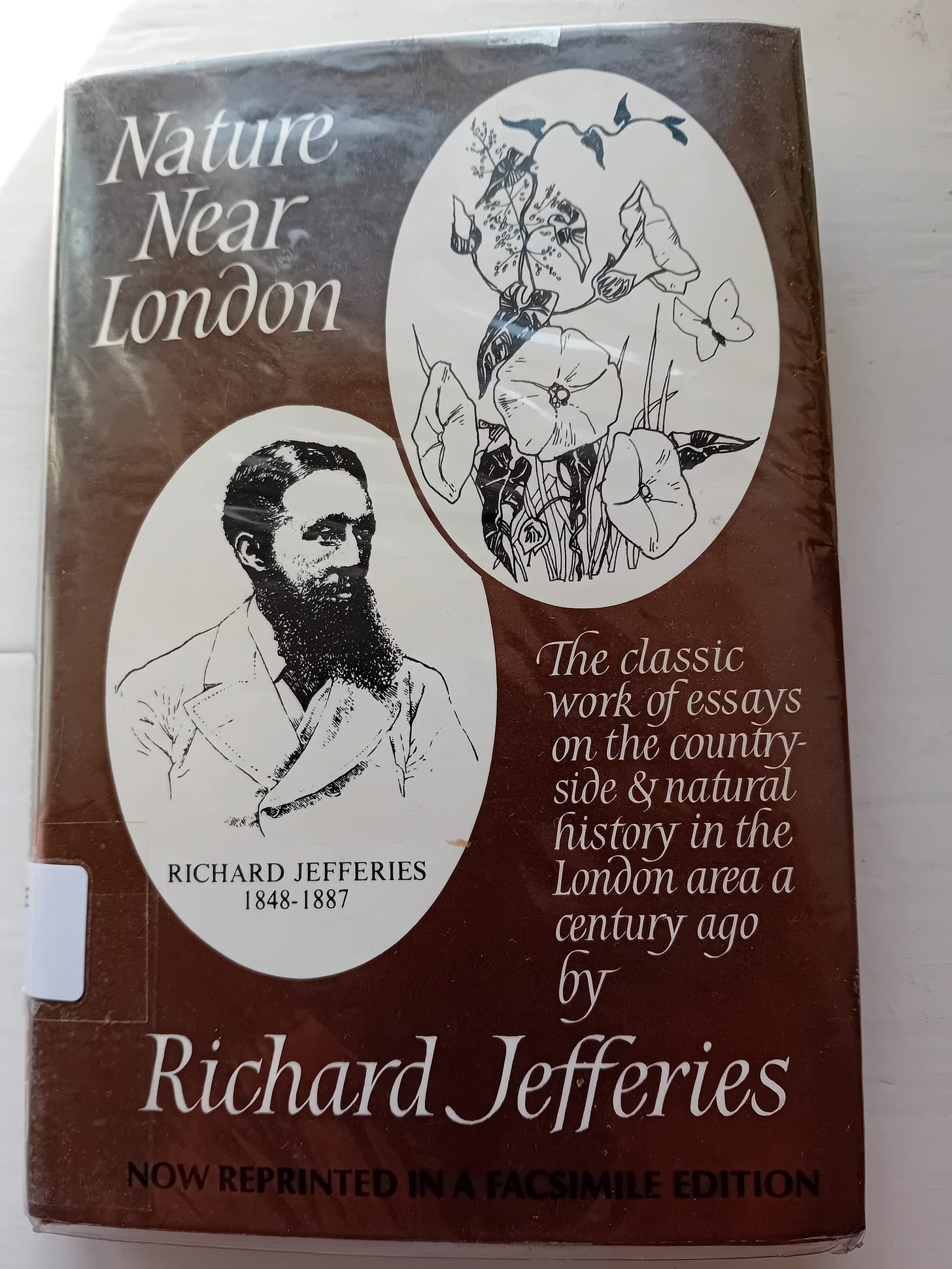

Until recently, the only one of these books I’d attempted was a science fiction novel, After London, which is set after some terrible catastrophe has wiped out most of the population of England and nature is gradually reclaiming the land. I liked the first section of the book which includes some beautiful descriptions of fields and towns becoming more and more filled with wildlife, but I didn’t enjoy the story which comes later and the book didn’t tempt me to read any more of Jefferies’ writing. However, I have recently read his book of essays about the countryside close to the capital, Nature Near London, and I wish I’d read it sooner because it well deserves its reputation as a nature writing classic and provides fascinating insights into the Victorians’ relationship with the natural world.

Jefferies wrote these essays while living in Surbiton between 1877 and 1882, having moved there in the hope that being closer to publishers in London would help him further his writing career. At the time Surbiton was right on the edge of the expanding capital, a place where rural was gradually transforming to urban and, as he had done throughout his life, Jefferies spent much of his time exploring the surrounding countryside. There were woods where nightingales sang nearby as well as fields, streams, heaths and commons, all of which he writes about in the essays in Nature Near London although in most cases he doesn’t include place names or specify the precise locations he writes about. In the preface for the book, he explains that this is “Because no two persons look at the same thing with the same eyes. To me this spot may be attractive, to you another; a third yonder gnarled oak the most artistic. Nor could I guarantee that every one should see the same things under the same conditions of season, time or weather….Everyone must find their own locality.” It’s a fair point and a modern writer might adopt a similar approach in an attempt to protect their favourite spot from being over-run but it’s a shame that it’s not possible to compare how the places he writes about have changed over time.

Towards the end of the book he does mention some specific places, particularly in he last few essays which describe his wanderings on the South Downs around Brighton and Eastbourne. There is also a really beautiful piece called “Herbs” extolling the virtues of Kew Gardens, a place Jefferies describes as a “great green book, whose broad pages are illuminated with flowers, [which] lies open at the feet of Londoners”. His focus is not on the Palm Houses which attract most visitors but on the Herbaceous Ground, “a living dictionary of English wild flowers”, and the opportunities that this provides to help people identify plants they may have seen elsewhere. Jefferies is worried that an increasingly urbanised population is losing important knowledge about the natural world and that “the names of many of the commonest herbs are quite forgotten”. It’s a concern he references in some of his other essays too and one which is even more relevant today.

In “Herbs” as well as describing in some detail the various different plants he sees at Kew, there is a particularly evocative section where he describes what he can hear:

“The delicious silence is not the silence of night, of lifelessness; it is the lack of jarring, mechanical noise; it is not silence but the sound of leaf and grass gently stroked by the soft and tender touch of the summer air. It is the sound of happy finches, of the slow buzz of humble-bees, of the occasional splash of a fish, or the call of a moorhen. Invisible in the brilliant beams above, vast legions of insects crowd the sky, but the product of their restless motion is a slumberous hum.”

It’s some years now since my last visit to Kew Gardens but sadly the sound I most strongly associate with it is that of planes flying overhead every few minutes on their way in or out of Heathrow. The modern world was already starting to intrude in Jefferies’ time and his appreciation of the silence is eventually interrupted by a steam launch passing on the river but it must have been wonderful to experience Kew when it could be described as a place where “the peace of green things reigns”.

The description of Kew is just one of many examples in the book which highlight how much of the natural world we have lost in the century and a half since Jefferies was writing. Nearly every essay is filled with long lists and descriptions of the wildlife he encounters, with a particular focus on wildflowers and birds. The pieces record a level of abundance that simply doesn’t exist anywhere in the UK now – in town or country. Here’s just one example: “Sparrows crowd every hedge and field, their numbers are incredible; chaffinches are not to be counted; of greenfinches there must be thousands.” Such sentences provide a stark contrast to the current situation when nearly every week seems to bring new evidence about the loss of species in England, such as this recent article about the decline in the number of bats.

Reading these essays provided a welcome opportunity to escape to a world filled with wildlife and, for the most part, I found the beautiful nature writing enough but I did occasionally wish Jefferies had spent a little more time discussing the implications of human activities for the natural world. Other than briefly considering whether the sewers and gas pipes associated with suburbanisation may be having a negative effect on trees, Jefferies doesn’t pay too much attention to the impact on other species of the changes he mentions such as the coming of the railways, new farming methods and the expanding suburbs. Nor does he offer any advice about what might need to change to reduce those impacts or even express much concern about the shooting of birds, something he mentions several times with a casualness that makes you appreciate just how commonplace this was in the nineteenth century. The one thing that really does seem to upset him is the types of trees and shrubs that are being chosen for planting in suburban gardens and on London’s streets. In “Trees about Town”, he rails against the dominance of foreign evergreens such as laurels and rhododendrons in the gardens of new houses just outside London. He is also very unhappy that plane trees have been selected for planting on the Thames Embankment and elsewhere in London, believing them “unfit for our country”.

There’s much more I could write about this book, but I’d encourage you to explore it yourself. The essays also contain some fascinating insights into a vanished world, one in which shoppers have to rush to get out of the way as drovers take fast-moving herds of cattle along suburban high streets, “mouchers” gather sacks of dandelions from the roadside in spring and Irish travelling families return to live in the same barns year after year “for the hoeing and the harvest”.

To finish….

…a few things I’d like to share:

Buried podcast: Both series of this podcast are really interesting, if a little depressing at times. They are written and presented by a couple of investigative journalists who have uncovered shocking evidence about illegal landfills (series 1) and the level of “forever chemicals” in the environment (series 2). The depressing bit is realising just how much some people are willing to ignore any potential harm to the environment when there’s a quick buck to be made.

The London Climate Resilience Review: This report commissioned by the Mayor of London, published last week, sets out 50 recommendations for ensuring the capital is better prepared for the impacts of the changing climate. It’s good to see there’s a strong emphasis on nature-based solutions including the important role that trees can play. The recommendation that seems to have got most attention is the proposal to charge people who pave over their front garden in recognition of the increased cost of dealing with the resulting increase in surface water runoff. This Guardian article has a good overview of this and some of the other key recommendations.

Nature Book Group: One of the main reasons I finally got round to reading Nature Near London is that it was chosen for discussion by the nature book group I belong to. For the past few years, we’ve been meeting every month to discuss books with a major nature theme (mainly non-fiction but we read novels occasionally too) and it’s been a great way of discovering books I might not have read otherwise (Thanks to Chris for suggesting this one!). We also have a related group on goodreads which is open to all and includes details of all the books we’ve read to date.

I’ve been stuck at home with a heavy cold for most of the last couple of weeks, hence the focus on a book for this piece. But I’m now fully recovered so I’ll be back to writing about something more active next time. If you’re new to Stories of Coexistence, you might want to have a look at some of my other pieces to get a feel for the kind of things I usually write about. Here’s a couple of suggestions:

Brimstone and Peacock

For almost half a century, thousands of people have been walking set routes, known as transects, every week between April and September and recording the number of butterflies they see. Or, at least they do, if the weather conditions are right. Too wet, cold or windy and the butterflies wo…

Hedge Benefits

One of the places I volunteer regularly with TCV Croydon is South Norwood Country Park where we’ve undertaken a range of tasks over the years - everything from coppicing willow around the lake and planting trees to path maintenance and building lots and lots of dead hedge…

Although I don't reside in Great Britain, your shared description. of nature are wonderful.

Thanks for sharing - sounds like a fascinating book. I might have to pick it up to see what he says about the South Downs near Brighton and Eastbourne! Hope you are feeling better. Thanks for sharing the Goodreads list - a good list!